Jùjú music

| Jùjú | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Yoruba music |

| Cultural origins | 1900s in Nigeria |

| Part of a series on |

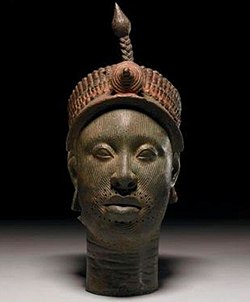

| Yorùbá people |

|---|

|

Jùjú is a style of Yoruba popular music, derived from traditional Yoruba percussion. The name juju from the Yoruba word "juju" or "jiju" meaning "throwing" or "something being thrown". Juju music did not derive its name from juju, which is a form of magic and the use of magic objects, common in West Africa, Haiti, Cuba and other Caribbean and South American nations. It evolved in the 1900s in urban clubs across the countries, and was believed to have been created by Abdulrafiu Babatunde King, popularly known as Tunde King. The first jùjú recordings were by King and Ojoge Daniel in the 1920s, when King pioneered it. The lead and predominant instrument of jùjú is the gagan, talking drum.[1] Although jùjú music was in its early development in the 1920s, the jùjú music genre did not emerge until the mid-1930s.[2] Jùjú music emerged in Lagos in 1932, and was influenced by palm wine guitar music.[3]

Some juju musicians were itinerant, including early pioneers Ojoge Daniel, Irewole Denge and the "blind minstrel" Kokoro.[4]

Afro-juju is a style of Nigerian popular music, a mixture of jùjú music and Afrobeat. Its most famous exponent was Shina Peters, who was so popular that the press called the phenomenon "Shinamania". Afro-juju's peak of popularity came in the early 1990s.

History

[edit]When jùjú music was first developing, groups often formed as trios.[5] This included a bandleader who sang and played the banjo, a tambourine player, and a sèkèrè player (gourd rattle).[5] Sometimes a fourth person would be added as a supporting vocalist.[5] By the end of WWII, jùjú bands were mostly quartets.[5] Following World War II, electric instruments began to be included, and pioneering musicians like Earnest Olatunde Thomas (Tunde Nightingale), Fatai Rolling Dollar, I. K. Dairo, Dele Ojo, Ayinde Bakare, Adeolu Akinsanya, King Sunny Adé.,[6] and Ebenezer Obey made the genre the most popular in Nigeria, incorporating new influences like funk, reggae and Afrobeat and creating new subgenres like yo-pop. Some new generation juju artistes include Oludare Olateju also known as Ludare, the son of Sabada juju music creator; Emperor Wale Olateju and Bola Abimbola. Although juju music, like apala, sakara, fuji and waka was created by Muslim Yoruba, the music itself remains secular. King Sunny Adé was the first to include the pedal steel guitar, which had previously been used only in Hawaiian music and American country music. Jùjú music was and is used for expressing cultural identity in Nigeria, especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s after the Second World War when Nigeria became independent from the United Kingdom.[7] This is when nationalism was at its highest in the country.[7]

Performance venue

[edit]Jùjú music is performed primarily by artists from the southwestern region of Nigeria, where the Yoruba are the most numerous ethnic group.[8] In performance, audience members commonly shower jùjú musicians with paper money; this tradition is known as "spraying".[9] The tradition of "spraying" involves a pleased recipient dancing toward the bandleader or praise singer and attaching money to their forehead.[5] This commonly serves as a primary source of income for musicians.[5] Some other sources of income include cash advances and record royalties.[5]

Music researcher Christpher Alan Waterman said that one of the centers of the performance of jùjú music is in Ibadan.[10] Most jùjú musicians are based in the zone of market forces. There are several contexts in which jùjú music is performed. Music was performed at hotels, nightclub, and university. The Hotels serve music halls and dance halls also. Most activity takes place after nine p.m., and the hotels are the center of Ibadan's economic structure. Jùjú performances often lasted for hours without any breaks and there were often competitions between localgroups.[5] There was a nocturnal sub-culture that developed in Lagos and even the most successful jùjú musicians had an ambiguous status.[5] The nighttime was known to be a time uncertainty in Yoruba traditions.[5] Spirits and witches were known to be most active at night, respectable families would tightly shutter their houses.[5] Many musicians would tell stories of strange things happening on their way to or from nocturnal performances.[5] Jùjú artist Tunde King even wrote some lyrics talking about the night. Musicians would also use their cigarette smoke to make a protective aura.[5]

Another context in which jùjú music is played is at celebrations called àríyá. King Sunny Adé performed at àríyá with his socio aesthetics.[11] These celebrations are parties which celebrate the naming of a baby, weddings, birthdays, funerals, title-taking, ceremonies and the launching of new property or business enterprises. Live music is crucial to the proper functioning of an àríyá.

Aesthetic

[edit]The musical elements of jùju music include its rhythmic foundations.[2] You will often hear complex rhythms like polyrhythms.[2] Percussion Instruments include the jùjú Drum (tambourine), talking drum (gangan), gourd rattle, agidigbo (type of xylophone) and guitar (plays both lead and rhythm roles).[2] Melodic and harmonic elementsinclude a call-and-response structure, improvisation, guitar and harmony and expressive vocal style.[2] Lyricalcontent and themes also include, praise singing, storytelling, and reflecting themes such as identity, community, life, spiritual beliefs, and social commentary.[2] Early styles of jùjú consisted of acoustic guitar or banjo, drums, gourd rattle, tambourine, vocals (call and response, harmonies, repetitive refrain).[7] Modern jùjú still consists of the basic structure but polyrhythmic percussion is more of an essential element now as well as other instruments and electric instruments such as, electric guitars, synthesizers, pedal steel guitars, talking drums, and sometimes saxophones.[7] Jùjú music can be influenced by different musical genres such as rock, funk and reggae.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rasaki's Drums and the rich rhythms of Nigeria's Yorubá

- ^ a b c d e f Alaja-Browne, Afolabi (1989). "The Origin and Development of JuJu Music". The Black Perspective in Music. 17 (1/2): 55. doi:10.2307/1214743.

- ^ Waterman, Christopher (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 1. Routledge. pp. 471–487.

- ^ Toyin Falola (2001). Culture and customs of Nigeria. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 173. ISBN 0-313-31338-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Waterman, Christopher A. (1990). Jùjú: A Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 55–81.

- ^ "King Sunny Ade: Juju legend launches radio station". Pulse News. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, Terry E.; Shahriari, Andrew (2020-10-20), "World Music: A Global Journey", World Music, Fifth edition. | New York : Routledge, 2020.: Routledge, pp. 300–318, ISBN 978-0-367-82349-8, retrieved 2025-03-08

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Valdés, Vanessa K. (2015). "Yoruba Traditions and African American Religious Nationalism by Tracey E. Hucks". Callaloo. 38: 234–237. doi:10.1353/cal.2015.0025. S2CID 143058809.

- ^ Graham, pgs. 592–593 Graham describes the origins of Peters' Afro-juju, the importance of Afro-Juju Series 1, the term Shinamania and the critical and commercial performance of Shinamania

- ^ Juju, Christpher A. Waterman Retrieved 26 December 2020

- ^ King Sunny Ade ariya Retrieved 26 January 2021

External links

[edit]- King Sunny Ade interview by Jason Gross from Perfect Sound Forever site (June 1998)

- "Sparkling Prince of Juju Music Called Ludare", Thisday, October 2016